[ad_1]

Chris Rauch was strolling previous cubicles on the annual ag present in Spokane final summer time when he noticed a big jar filled with basalt powder. A close-by signal urged him to unfold it on his croplands to assist enhance soil pH.

Rauch seemed on the grey mud and shook his head.

“That’s loopy,” he thought. “Why would I need to put even extra rocks in my fields?”

Rauch grows dryland wheat within the rolling gold-brown hills surrounding the Pendleton, Oregon, municipal airport. His farm lies on the Columbia Plateau, a 63,000-square-mile basin shaped by historic basalt lava flows. On the finish of the final Ice Age, retreating glaciers scoured the bedrock, leaving a wake of grit and gravel to type the deep loess soil.

Not a lot rain falls on this grassland habitat. Some years, it’s 9 to 12 inches, however these days, it’s extra like 6 to 9. Pre-cultivation, the area owed the wholesome pH of its soils to the fortunate coincidence of sitting atop a volcanic mattress. Nonetheless, the topsoil is powerless to counteract the acidifying impact of ammonia-based fertilizers. Over time, this has brought on pH ranges to drop to five and under, in response to Dr. Francisco Calderon, director of the Columbia Basin Agricultural Analysis Heart.

“It’s not a widespread downside but, but it surely’s rearing its ugly head in some locations,” says Calderon.

Just a few weeks after the ag present, Rauch received the most recent outcomes of his soil pH assessments: 5.3. He recalled the message from the ag present sales space, run by an organization referred to as UNDO. The crushed rock raised soil pH ranges. And it was free.

His first thought was, why? It appeared too good to be true. But the extra he learn, the extra it appeared legit.

“You may’t beat zero,” he lastly determined, and gave UNDO a name.

Chris Rauch’s Oregon farm lies on the Columbia Plateau, a area that has seen growing ranges of soil acidity. (Picture courtesy of Chris Rauch)

Rauch is certainly one of many farmers taking an opportunity on a brand new course of referred to as Enhanced Rock Weathering, or ERW. Startup firms throughout the nation are bringing crushed volcanic rock to farmers’ fields and spreading it to enhance their soils. The rock powder, often basalt, is commonly scavenged from native mines or quarries, the place it exists as a waste by-product. ERW firms accumulate the rock powder, typically milling it additional to scale back the grain dimension. Then they truck it to farms, the place it’s used rather than ag lime. Research present that volcanic rock mud can increase the pH of overworked soils, enhancing productiveness. And since enhanced rock weathering is taken into account a type of everlasting carbon dioxide elimination, the startups can promote “carbon credit” to massive companies like Microsoft that need to cut back their carbon footprint and present they’re appearing on local weather change.

The strategy is predicated on a long time of scientific analysis that exploits what some name “earth’s thermostat.” Carbon dioxide within the ambiance naturally reacts with water to type a weak acid. This acid then bonds with minerals in volcanic stone and completely removes the CO2 from the air. Geochemists found that this pure carbon cycle may very well be accelerated by crushing the rock, which exposes extra of its reactive floor. A research revealed final month by the American Geophysical Union acknowledged that ERW had the potential to sequester greater than 200 gigatons of CO2 in a 75-year interval. That may put a small however significant dent on the earth’s CO2 emissions, which at the moment stand at round 37 gigatons per yr.

Saving the world wasn’t on Rauch’s thoughts as he watched a spreader rumble over his fields, delivering what seemed and gave the impression of soiled sleet. Rauch was anxious about seeding, soil compaction and whether or not he’d find yourself with one large gravel pile. To his shock, the basalt blended together with his soil as if it have been only one thing more that had blown in on the wind.

Chris Rauch’s son Andre pulls soil samples from their dryland wheat farm. (Picture courtesy of Chris Rauch)

In keeping with Zoe Younger, UNDO’s native agent within the Pacific Northwest area, Rauch’s skepticism is a standard response. At first, farmers assume it sounds loopy. Then they need to know why they’re being provided one thing for nothing.

“It appears sneaky,” she says.

Younger attributes farmers’ doubts to their fraught historical past with well-meaning packages.

“The inexperienced trade has taken benefit of farmers in a variety of methods,” she says. Farmers be part of waitlists for photo voltaic panels in alternate for not farming their fields, then the photo voltaic firms by no means present up. Or they’re tricked into signing multi-year contracts.

“Farmers can see the profit for his or her farm,” Younger explains. “However they are saying, ‘You’re simply cashing in on the brand new bullshit market.’”

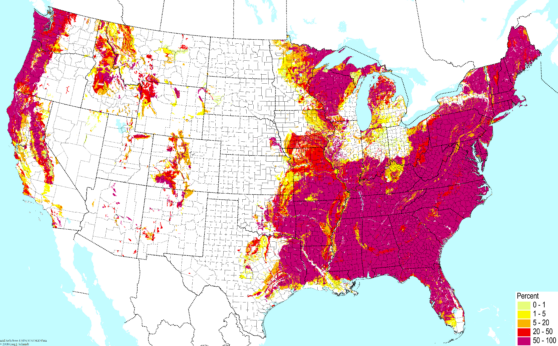

Michigan, the state formed like a mitten, has acidic soils up in the direction of its fingertips and alkaline soils down in its palm, the place agricultural advisor Jesse Vollmar lives. The clay loam soil there’s comparatively good, with a pure pH between 6.5 and seven, and rainfall is an enviable 20 inches per yr. Whereas these Midwest circumstances could sound excellent for farming, years of tilling and heavy fertilizer use have taken their toll.

Vollmar is from a 5th-generation farm household. He started his profession serving to different farmers enroll in federal sustainable agriculture packages and noticed their struggles firsthand. Farmers wanted years’ price of tillage and canopy crop information to be eligible. As soon as enrolled, they have been required to conduct common soil assessments. Payout got here solely after a decade.

Two years in the past, Vollmar started working with Lithos Carbon, a small ERW firm based mostly in Seattle. He likes that ERW firms do all of the soil assessments and record-keeping and require solely a one-year dedication. Vollmar stays a powerful proponent of regenerative farming and believes the 2 ought to be practiced collectively. However in his view, the economics of ERW can’t be beat.

“It’s only a no-brainer for farmers,” he says. “The toughest half is maintaining with demand.”

Virginia farmer Rick Bennett contracted with Lithos Carbon to check ERW on his soybean fields. (Picture courtesy of Rick Bennett)

Just a few states over within the Piedmont area of southern Virginia, farmer Rick Bennett is a Lithos shopper. Bennett grows corn, candy beans, soybeans and cereals on previous tobacco land that has seen two centuries of heavy use. The soil, a mix of silt and clay, is acidic and low in natural matter.

Final spring, Bennett selected a very acidic plot and contracted with Lithos to deal with it. The corporate created a sequence of take a look at strips in order that Bennett might observe the distinction, and he planted soybeans over your complete space. 5 months later, Bennett doesn’t see an excessive amount of distinction, however he says he’ll know for sure when he places a mix within the discipline.

“It’s not about seems to be however the variety of pods and beans within the pods.”

Former skilled soccer participant turned farmer Jason Brown additionally tried basalt powder final spring on First Fruits Farm, his 1,000-acre farmstead in Louisburg, North Carolina. Brown donates a lot of what he raises to assist combat starvation in his neighborhood. However he understands the razor-thin budgets of his fellow farmers, which forces a lot of them to select and select which crops they’ll afford to develop. Enhanced rock weathering may also help ease the crunch, says Brown.

“It’s all-around mutually helpful, however for farmers, it is a actually massive deal,” Brown explains. “Most instances, we’ve to put in writing very massive checks for each modification we add to our soils. This is likely one of the uncommon instances when farmers not solely get a break however a profit.”

Brown says that native farmers are ready to see whether or not first adopters like him get higher soil take a look at outcomes—and, importantly, a examine within the mail for permitting liming on their fields.

“As soon as that occurs, I promise you that each farmer from Virginia to South Carolina goes to be ready in [the] queue to enroll.”

Jason Brown is testing basalt powder on his 1,000-acre farmstead in Louisburg, North Carolina. (Picture: First Fruits Farm/Fb)

Basalt is the most typical volcanic rock on earth, coating the flooring of most seas, underlying areas such because the Columbia Plateau, and jutting out in unusual columnar formations such because the Large’s Causeway in Eire. However volcanoes spew out many sorts of molten rock. One other volcanic mineral is olivine, a greenish stone that contains the vast majority of earth’s higher mantle. Research present that olivine has the next capability than basalt to seize CO2 and could also be faster—a minimum of initially—to change soil pH.

The Princeton-based firm EION makes use of olivine to put down rock mud within the steamy fields of the Mississippi River Delta area. Soils there are previous, crimson and acidic, like soils within the tropics. The panorama is a patchwork of timber, pasture, row crops, looking habitat and buffer strips—a really perfect mannequin for managing agricultural land for a number of ends, in response to Adam Wolf, founder and CEO of EION.

“They’ve an appreciation for the pure world,” says Wolf. “It’s not as reductionist as in locations like California, the place you see huge landscapes dominated by one crop.”

Warmth and humidity velocity the response of rock weathering, and EION makes use of that plus olivine’s excessive CO2 seize charge to do extra with much less. The corporate spreads two to a few tons of olivine per acre as an alternative of 9 or 10 tons of basalt. Nonetheless, as a result of native olivine sources don’t exist, EION should import the olivine by ship from Norway. As soon as it reaches the huge river system of the Mississippi, it may be milled and distributed to farms as distant as North Dakota.

Dan Prevost is a Mississippi farmer and agricultural advisor for EION. He rents patches of “used and abused” land close to his dwelling in south-central Mississippi and helps native farmers check out rock mud of their fields.

“I don’t personal any land of my very own, so I get the land no one else needed,” Prevost jokes.

“Rebuilding the soil is my primary precedence.”

A map of acidic soil ranges throughout the US. (Courtesy of BONAP.org)

Like Vollmar, Prevost began in regenerative farming and is aware of the vital significance of soil pH.

“When you get a bit of farmland, the very very first thing you do is get your pH proper,” says Prevost. ‘That optimizes nutrient availability. You probably have a low pH, you possibly can put all of the fertilizer on that you really want, however the vitamins aren’t going to be accessible.”

Prevost examined olivine on his land final spring. He selected a poor, acidic soil part and laid down two tons per acre, then planted corn on each handled and untreated plots. Though he’s nonetheless ready for remaining information, Prevost says that the corn on the handled aspect was “tremendous darkish inexperienced” in comparison with the untreated part.

Prevost has loads of farmers prepared to attempt ERW, however, like Younger and Vollmar, he understands their preliminary reluctance. Farmers are consistently harangued in regards to the newest ‘sizzling matter,’ he says, from sedimentation and erosion to pesticides, nutrient loading in waterways and declining irrigation aquifers. Whereas all are essential, the sheer amount may be overwhelming.

“Now we’re speaking about local weather change,” says Prevost. “Subsequent on the listing goes to be biodiversity. Farmers get jaded with issues fairly fast.”

Local weather packages additionally get a foul rap within the Deep South as a result of they usually promise unachievable carbon seize ranges. Soil microbes cycle sooner there than in colder, drier climates, says Prevost. Their carbon is launched again into the ambiance once they die, defeating the packages’ targets.

Prevost talks about improved pH, micro-nutrients and crop yields in his work with farmers reasonably than saving the planet.

“Sometimes, we don’t discuss local weather change as a result of that’s simply one other sizzling matter,” he says. “However all people can just about agree that issues are completely different. We’re getting extra intense climate patterns—drier dries and wetter wets and extra frequent hailstorms.”

Dan Prevost is a Mississippi farmer and agricultural advisor for EION, an organization that makes use of olivine to put down rock mud within the Mississippi River Delta area. (Picture courtesy of EION)

Throughout the nation, farmers are testing a brand new technique of enhancing the well being and productiveness of their soils. From the semi-arid excessive desert of japanese Oregon to the subtropical floodplain of the Mississippi Delta, they’re partnering with new firms that provide an apparently reputable something-for-nothing deal. Whether or not soils are naturally acidic or made so by man, volcanic rock mud seems to assist restore wholesome soil pH ranges and, together with it, soil fertility and productiveness.

The following few years ought to inform whether or not enhanced rock weathering turns into yet one more bothersome “sizzling matter” or catches on as a boon to each farmers and the planet. The lab analysis proves ERW’s potential; the primary discipline information is coming in with the autumn harvest.

Out in Pendleton’s golden wheat fields final month, Chris Rauch obtained the most recent soil pH take a look at outcomes: 5.7-5.8, considerably greater than final yr’s studying of 5.3.

Rauch was shocked.

“Whether or not it’s the rock or that the celebrities lined up that day, it’s too quickly to know for positive,” he says.

“However it’s a development in the suitable course.”

[ad_2]

Source link